American Journeys

American Journeys is framed by a two-month drive from San Francisco to New York. Documentary photographer, Jessie Parks, and journalist, Katy Long, interviewed and photographed over 100 migrants, refugees, and "locals" in 21 states, documenting how immigration has shaped communities and understandings of national American identity.

The project explores the different contexts of welcome and inclusion—from wealthy coastal cosmopolitan cities to small rust-belt rural communities.

The project includes not only the voices of immigrants but also “locals” living in the communities visited, to understand their thoughts about what it means to be American today, and who should be allowed to belong. There is a particular interest in understanding how local dynamics intersect with national conversations, and the impact on recent US federal policy changes—resulting in increased fears of deportation for many immigrants, reduced refugee resettlement numbers, and narrowing visa opportunities for workers and businesses.

Follow along at the ODI Journey Across America Blog

Katy and Jessie first collaborated in 2017 on a feature for The Guardian. This work focused on a small community, Clarkston, Georgia. It documented how locals welcome refugees to the Deep South.

Katy has spent 12 years working on refugee and migrant issues, first as an academic researcher in the U.K., and then working on policy development and evaluation (UNHCR, The Sutherland Report).

Jessie's work as a photographer has focused on giving a voice to the unheard. In recent years she has been primarily concerned with documenting the lives of immigrants and the displaced, both close to her native Atlanta, and in Iraqi Kurdistan where she lived for several months in 2016 and 2017.

For images and updates, follow us on Instagram @americanjourneysproject or @missjessieparks

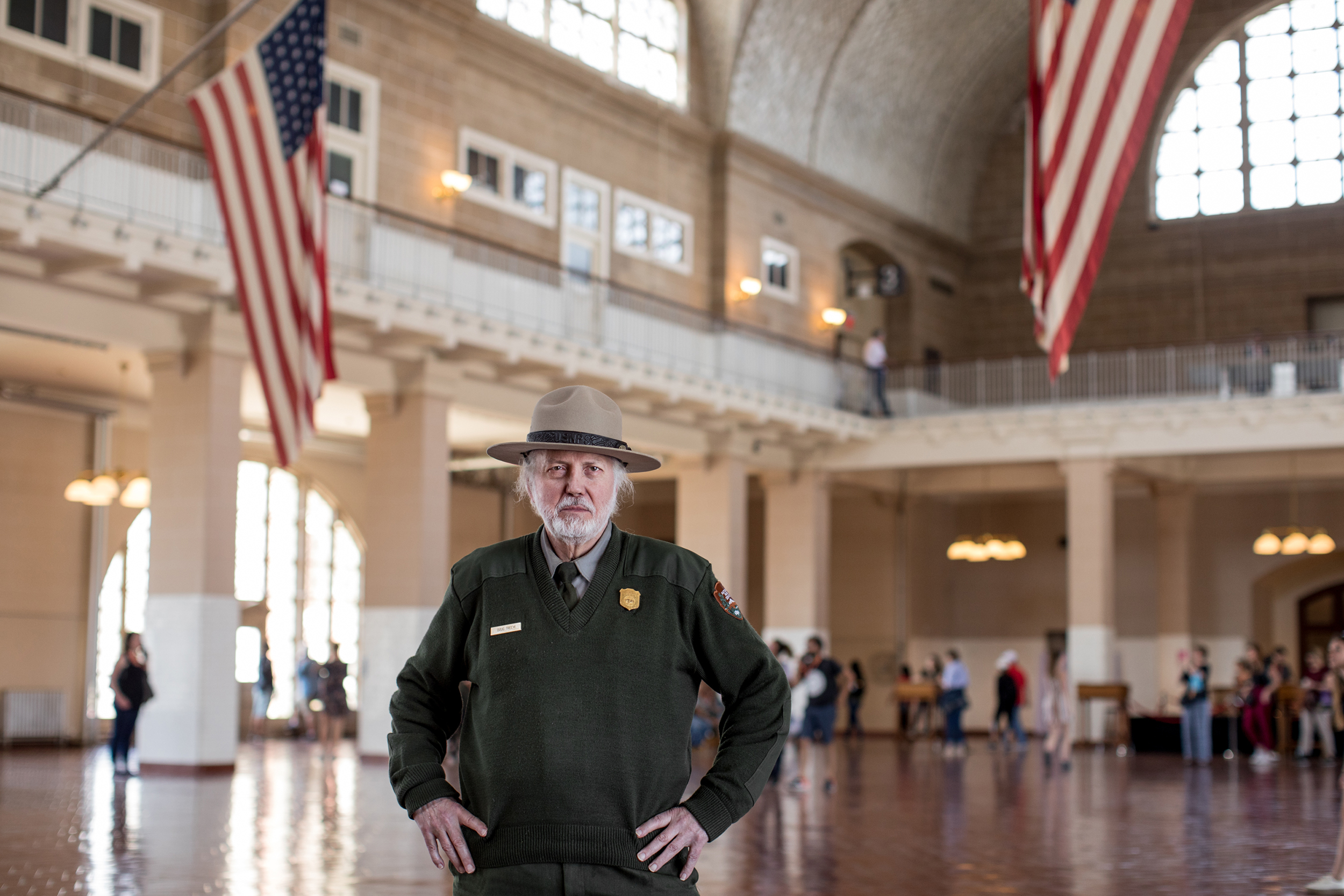

Photo Captions Written by Katy Long, Photographs by Jessie Parks

Immigrants from 22 different countries prepare to take the oath of allegiance and become new US citizens in Roanoke, Virginia

We met Mark on a sunny afternoon, mowing lawns in a trailer park in Princeton, West Virginia. He wasn't bothered about immigration -- "long as it's legal" -- but he spoke enthusiastically about Donald Trump's economic agenda: "he's bringing coal back. That's what people care about round here. Bringing the coal back, bringing jobs back."

Between 1929 and 1936, Los Angeles deported up to 400,000 Mexican Americans — US citizens — were forcibly “repatriated” to their “home” in Mexico. The policy failed: Los Angeles today has the largest population of Mexicans in the world outside Mexico. One such immigrant, Diego, manages a bric-a-brac store in East Los Angeles, an area of the city which today is 99% Latino.

Growing up in Tanzania, Gulshan Harjee dreamed of becoming a doctor. Instead, as Tanzania moved to expel its Asian citizens, she found herself stateless. After her studies in Iran were cut short by the 1979 Revolution, she eventually settled in the US and made her way to medical school. Three years ago, she co-founded the Clarkston Community Health Centre, where anyone without health insurance -- regardless of their legal status -- can seek medical or dental treatment. The line of patients waiting for the Sunday clinic can sometimes stretch around the block

Elderly immigrants play Xianqi (Chinese chess) in Portsmouth Square, San Francisco. The city's Chinatown is still the most densely populated urban area west of Manhattan. Many families live in single rooms: the square is the community's garden.

Princeton, West Virginia is home to a small but vibrant Islamic community. Nearly all those attending Friday prayers are medical doctors, who arrived from Pakistan and India in the 1970s. Twenty years ago, 40% of the doctors in the region were foreign-born. Now this community of Muslim professionals is nearing retirement, and their children -- educated American professionals -- have left the rural rustbelt for the cities.

In New Orleans' Lower Ninth Ward, all homes were uninhabitable after the flooding that followed Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The displaced were largely working-class black families, some of whom had owned the title to the land since emancipation. Laura Paul, director of lowernine.org, works to help these displaced Americans rebuild their homes, but 13 years later only around 1 in 3 have been able to return.

Mesingana never intended to come to America, but then his sister asked him to help with her application for the Diversity Visa lottery. He decided he might as well apply too. Then his number came up. The chance to leave Ethiopia and come to America was an opportunity not be missed, but Mesingana had to leave his girlfriend behind. Six years later - and just three weeks before we met them - she was finally able to join him in Clarkston, Georgia.

Travis Stringfellow runs an oyster shucking business in Bayou la Batre, Alabama. Like most of the fishing industry on the Gulf Coast, he's dependent upon migrant laborers. In the 1970s Vietnamese boat people settled here: now, it's the turn of Hondurans

Nashville has at least 15,000 Kurdish residents, more than any other US city. We spent a day at the Kabob House restaurant, a central meeting place in "Little Kurdistan", drinking mint tea and listening to stories of Southern Kurdish hospitality.